Why are bees making less honey? Study reveals clues in five decades of data

The study found that climate conditions and soil productivity — the ability of soil to support crops based on its physical, chemical and biological properties — were some of the most important factors in estimating honey yields. Credit: Arwin Neil Baichoo/Unsplash. All Rights Reserved.

By Katie Bohn

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — Honey yields in the U.S. have been declining since the 1990s, with honey producers and scientists unsure why, but a new study by Penn State researchers has uncovered clues in the mystery of the missing honey.

Using five decades of data from across the U.S., the researchers analyzed the potential factors and mechanisms that might be affecting the number of flowers growing in different regions — and, by extension, the amount of honey produced by honey bees.

The study, recently published in the journal Environmental Research, found that changes in honey yields over time were connected to herbicide application and land use, such as fewer land conservation programs that support pollinators. Annual weather anomalies also contributed to changes in yields.

The data, pulled from several open-source databases including those operated by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) National Agricultural Statistics Service and USDA Farm Service Agency, included such information as average honey yield per honey bee colony, land use, herbicide use, climate, weather anomalies and soil productivity in the continental United States.

Overall, researchers found that climate conditions and soil productivity — the ability of soil to support crops based on its physical, chemical and biological properties — were some of the most important factors in estimating honey yields. States in both warm and cool regions produced higher honey yields when they had productive soils.

The eco-regional soil and climate conditions set the baseline levels of honey production, while changes in land use, herbicide use and weather influenced how much is produced in a given year, the researchers summarized.

Gabriela Quinlan, the lead author on the study and a National Science Foundation (NSF) postdoctoral research fellow in Penn State’s Department of Entomology and Center for Pollinator Research, said she was inspired to conduct the study after attending beekeeper meetings and conferences and repeatedly hearing the same comment: You just can’t make honey like you used to.

According to Quinlan, climate became increasingly tied to honey yields in the data after 1992.

“It’s unclear how climate change will continue to affect honey production, but our findings may help to predict these changes,” Quinlan said. “For example, pollinator resources may decline in the Great Plains as the climate warms and becomes more moderate, while resources may increase in the mid-Atlantic as conditions become hotter.”

Co-author on the paper Christina Grozinger, Publius Vergilius Maro Professor of Entomology and director of the Center for Pollinator Research, said that while scientists previously knew that many factors influence flowering plant abundance and flower production, prior studies were conducted in only one region of the U.S.

“What’s really unique about this study is that we were able to take advantage of 50 years of data from across the continental U.S.,” she said. “This allowed us to really investigate the role of soil, eco-regional climate conditions, annual weather variation, land use and land management practices on the availability of nectar for honey bees and other pollinators.”

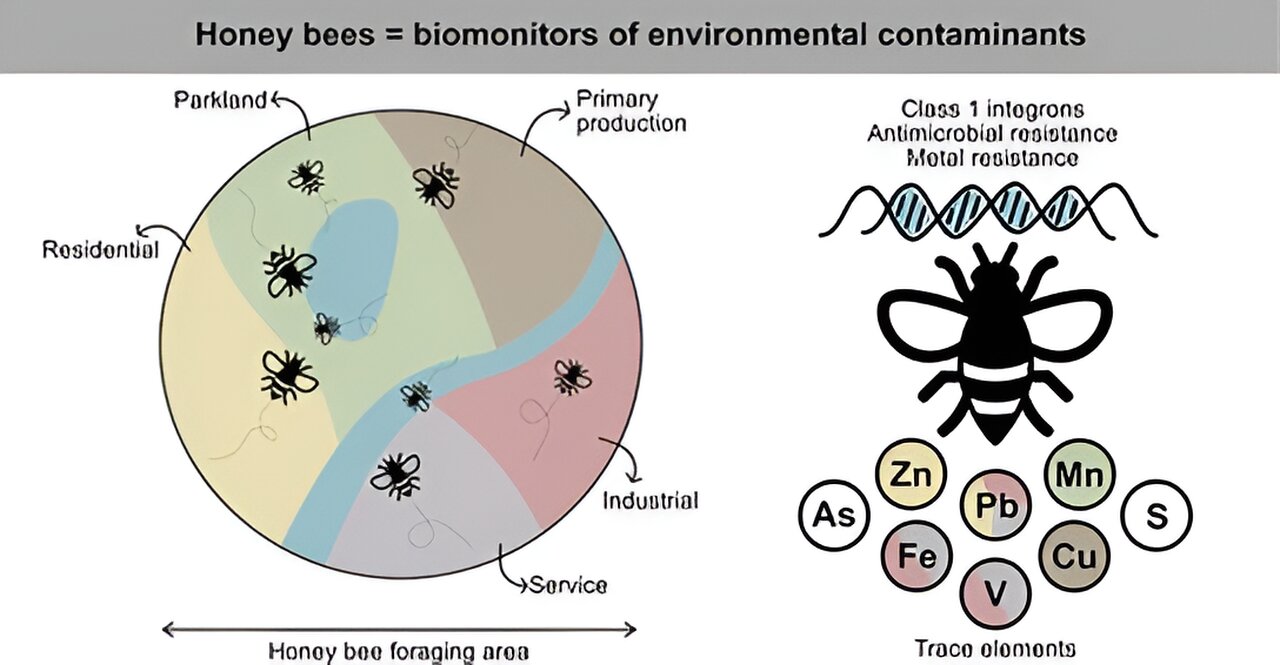

One of the biggest stressors to pollinators is a lack of flowers to provide enough pollen and nectar for food, according to the researchers. Because different regions can support different flowering plants depending on climate and soil characteristics, they said there is growing interest in identifying regions and landscapes with enough flowers to make them bee friendly.

“A lot of factors affect honey production, but a main one is the availability of flowers,” she said. “Honey bees are really good foragers, collecting nectar from a variety of flowering plants and turning that nectar into honey. I was curious that if beekeepers are seeing less honey, does that mean there are fewer floral resources available to pollinators overall? And if so, what environmental factors were causing this change?”

For Quinlan, one of the most exciting findings was the importance of soil productivity, which she said is an under-explored factor in analyzing how suitable different landscapes are for pollinators. While many studies have examined the importance of nutrients in the soil, less work has been done on how soil characteristics like temperature, texture, structure — properties that help determine productivity — affect pollinator resources.

The researchers also found that decreases in soybean land and increases in Conservation Reserve Program land, a national conservation program that has been shown to support pollinators, both resulted in positive effects on honey yields.

Herbicide application rates were also important in predicting honey yields, potentially because removing flowering weeds can reduce nutritional sources available to bees.

“Our findings provide valuable insights that can be applied to improve models and design experiments to enable beekeepers to predict honey yields, growers to understand pollination services, and land managers to support plant–pollinator communities and ecosystem services,” Quinlan said.

To learn more about the land use, floral resources and weather in specific areas, visit the Beescape tool on the Center for Pollinator Research website.

David A.W. Miller, associate professor of wildlife population ecology, was also a co-author on the study.

The NSF Postdoctoral Research Fellowship in Biology Program and the USDA National Institute Food and Agriculture’s Pollinator Health Program and Data Science for Food and Agricultural Systems Programs helped support this research.

We are here to share current happenings in the bee industry. Bee Culture gathers and shares articles published by outside sources. For more information about this specific article, please visit the original publish source: Why are bees making less honey? Study reveals clues in five decades of data | Penn State University (psu.edu)